Happenings at the KHM

The Importance of Temporary Exhibits

Whose stories get told in a museum?

Who gets to tell those stories?

Who has the control of those stories?

These questions do not have simple answers when it comes to museum exhibition practices. The Kodiak History Museum has a simple answer in the vehicle of our temporary exhibit program: KHM’s temporary exhibits are about Kodiak and created by and for all of Kodiak.

This flipping of the script, handing over curatorial control to the community, is part of KHM’s recent work to be more inclusive and accessible to the community we serve. By offering the museum’s platform and resources, the community partners who propose the exhibits have the opportunity to control their own curatorial narrative in telling their story and feeling heard by the broader community. Museum staff work to research their ideas, offer objects or archival documents from within the KHS collection, and assemble the vision of the community partners into each exhibit. The development of each exhibit begins with our community, and this spirit continues throughout the exhibit design process – KHM is the platform for and facilitator of our Kodiak community’s stories and ideas.

Every temporary exhibit is complemented by a variety of programs chosen by our community partners and developed as a partnership between KHM and community program facilitators. These programs complement the material and topics presented in each temporary exhibit, and they are designed to engage the visitor on a deeper level than what is afforded by the exhibit format.

We recognize that the amount of time and effort required of community members is significant. KHM makes this exhibit process more equitable by providing an honorarium to our community partners and program facilitators.

For more information about our temporary exhibit program and how to be involved, visit our website.

Update: The KHM Baleen Mystery

This blog post is guest-written by Dana Wright. Dana is a Marine Science and Conservation PhD student at Duke University. In May 2022, Dana spent two weeks at KHM obtaining baleen samples from KHM for her dissertation. Dana’s dissertation uses different methods, including stable isotope analysis, to investigate gaps in the life history of the critically endangered eastern population of the North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica). Dana came to KHM to obtain samples from baleen plates in KHM’s collection that have little to no background information. In the process of her research and analysis, Dana ascertained which whale species that KHM’s baleen came from and gained important insights into each whale’s diet and movement patterns.

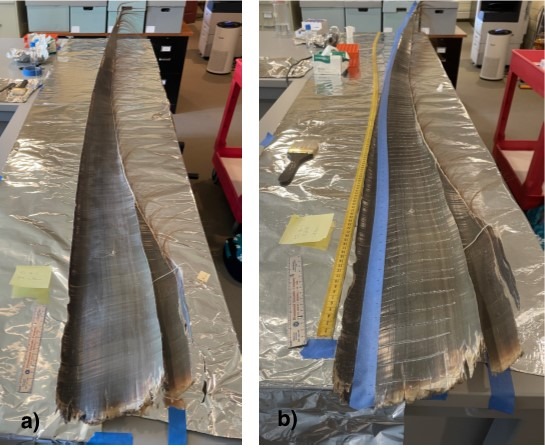

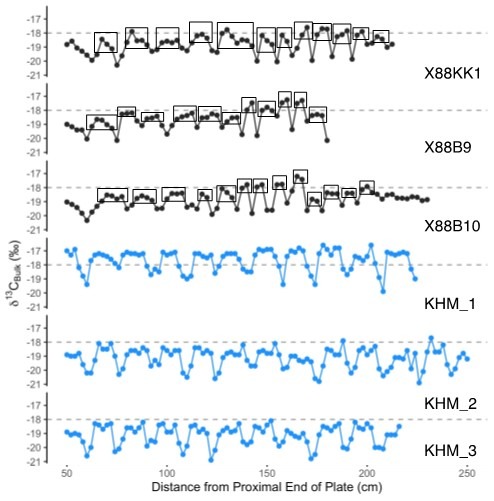

“Cama’i! My name is Dana, and I’m the PhD student that visited Kodiak this past May to sample three baleen plates at the Kodiak History Museum (KHM). I’m writing to share the results of this research effort. To jog your memory, I came to the Rock in hope of finding baleen plates from the critically endangered North Pacific right whale to learn about their migration. As part of this effort, I sampled three KHM plates to conduct a biogeochemical analysis called stable isotope analysis, which we hoped would tell us if the plates came from right whales or their northern cousin, the bowhead whale. We knew these plates were not from humpback whales or gray whales, because their baleen is much shorter. We believed this technique could answer our question, because bowheads spend all year at higher latitudes, and therefore, should have a different chemical signature than right whales. We also hypothesized that the three KHM plates could be from right whales, because right whales were harvested from the Port Hobron Whaling Station. In fact, the largest female ever landed and processed at a shore-based factory occurred at Port Hobron (62 feet!). Given that only six North Pacific right whale baleen plates currently exist in the United States, the discovery of any new plate would be invaluable.

Baleen plates grow continuously from the upper gum of right whales in lieu of teeth. (Baleen is made of the same stuff as our hair and fingernails – keratin!) Therefore, the baleen acts as a chronological recorder of the whale’s diet and movement. As a result, I collected tissue every 2 cm from end-to-end for each plate, which allowed me to reconstruct years of the whales’ ecological lives.

After collecting the samples, I headed to the University of New Mexico to process and analyze the tissue on a gas chromatograph. This machine turns the powered baleen into gas via combustion and then measures the ratio of stable isotopes in the sample. The machine can run approximately 50 samples in a day, and we had over 300 samples to run because the baleen plates were so long (> 2 meters)! I anxiously waited for the gas chromatograph to process each sample, hopeful that one of these plates could be from the elusive North Pacific right whale. As I waited, I reflected on my time on the Rock. Suspiciously nice spring weather combined with warm conversation and inviting smiles flooded back to me – along with the aroma of fresh coffee and cookies from Java Flats. This summer project would not have been possible without the help of numerous staff and scientists at the KHM and the NOAA facility on Near Island. Once the samples were processed, I sat down to plot the data, hot coffee in hand.

We discovered three things about the KHM baleen plates:

- Oscillations along the plate support a hypothesis of annual migrations

- Each plate came from a different individual whale

- All plates appear to be from bowhead whales

Oscillations along the plate support a hypothesis of annual migrations

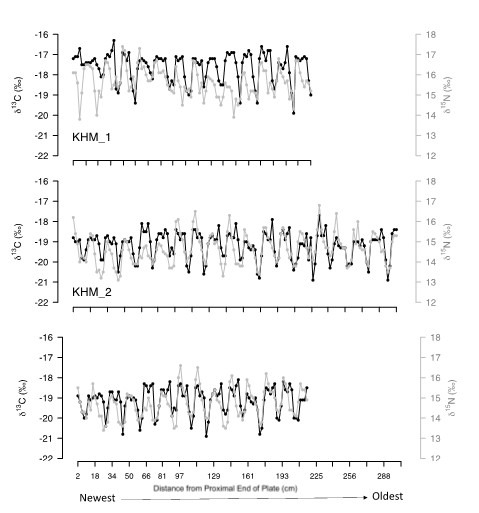

Plotting the data for each plate as a time-series, I noticed two things right off the bat. First, each plate consists of repeated oscillations that look stereotyped (i.e., occur at regular intervals along the baleen plate; Figure 2). Second, the oscillations in carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios follow the same general trend. Together, these observations support that these whales underwent annual migrations, with KHM 2 reflecting 17 migrations!

Each plate came from a different individual whale

Next, I noticed that the oscillations are not identical for each plate, so I hypothesized that these plates came from three different animals. I drew this conclusion, because we know that the baleen plates in an individual whale’s mouth grow at the same rate, and I sampled each plate at the same interval (2 cm). In addition, the trend in nitrogen relative to carbon varied slightly for each plate along the time-series. The difference in pattern among the plates support that the growth rate, migratory timing, physiology, and/or diet varied slightly for each whale over the period reflected in the baleen.

All plates appear to be from bowhead whales

Bowhead whales undergo annual migrations that follow the sea ice, oscillating between summer feeding in the Beaufort Sea to overwinter feeding and breeding in the northern Bering Sea. The oscillations on the KHM plate are stereotyped. Assuming each oscillation is an annual migration, we can conclude the baleen grew, on average, 24 cm/year for each animal, which is the same growth rate of bowhead whales harvested from Alaskan subsistence whaling. In addition, the shape of each annual cycle holds a clue – the dome shape of the maxima of each oscillation and spiky shape of the minima. The maxima shape supports that the baleen grew fast while the whale was in a similar geographic region (likely because the animal was eating a lot!), and the minima suggest slower growth during a period the whale was moving and eating proportionally less. Comparing this shape to Alaskan bowhead whales, the maxima and minima are similar (Figure 3). Because we know the domed maxima on the Alaskan bowhead plates reflect heavy winter feeding in the northern Bering Sea, we can hypothesize the domed maxima of the KHM plates also reflect winter feeding in the northern Bering. Together, these data support that the three KHM plates are likely from bowhead whales. Nevertheless, we hope to run genetic studies to confirm the species for each plate.

Through this blog post, I hope that I’ve shared one of the dozens of ways that museum collections can be used in scientific studies to learn about our world. While we have yet to uncover a North Pacific right whale baleen plate on Kodiak Island, I am cautiously optimistic that plates are out there.

Quyanaa, Kodiak!”

Caring for Art at the Museum

The Kodiak History Museum cares for hundreds of artworks. It is our job to collect and preserve information about each artwork and make it accessible for years to come.

Each artwork in KHM’s collection has an associated file with all of the information we have about the piece. We continually add information to these files, which in turn enriches the history and understanding about each object in our collection and provides new perspectives about how to display, interpret, and care for the piece.

On August 25, Kodiak artist Robert Tucker and friends, visited our collections research space to see a piece he carved 17 years ago. The piece, “Esquire of the Sea”, is a 4-foot long whale carved out of walnut wood. Through this visit, Tucker provided more information that enhances our understanding of the artwork and how to best care for it in the future.

You can listen to Robert Tucker explain about his inspiration, process, and wishes for this artwork for the future here.

This artwork was purchased with grant funds from the Museums Alaska Art Acquisition Fund with generous support from the Rasmuson Foundation.

Temporary Exhibit Model

In Spring 2022, the Kodiak History Museum debuted a new model for our temporary exhibit gallery. This blog post contains all you need to know about our new temporary exhibit program, how to be involved in the exhibit process, and any other facts!

The Program

KHM’s temporary exhibit program is social justice-oriented and community-based. In our new temporary exhibit program, KHM is working to replace the single authoritative voice in exhibits with that of many voices and perspectives in an effort to assert our relevance to the community of Kodiak and to find our place in contemporary Kodiak as a rebranded museum.

Our program is founded within the social justice in museums and decolonization movements. These movements recognize that museums have traditionally acted as gatekeepers of knowledge, parsing information out as warranted and to serve political needs. As a result, the museum culture in the US was based on the norms of dominant society and institutionally marginalized those not part of the dominant society. However, museums can become sites for social inclusion by working to address social issues with community partners. Efforts toward inclusivity allow museums to be more socially conscious institutions, especially in exhibit interpretation.

Our work with this program is also centered within the Museums Are Not Neutral movement. Museums have long been considered to be repositories – places where objects are held. However, museums are not just repositories; they are places when objects are interpreted through exhibits and educational programs. In other words, they are not apolitical or neutral; there is always some interpretation or bias of opinion. Museums today are currently undergoing a rapid change in interpretation; they are moving from offering a temple of knowledge for the already educated to a forum for the public where learning is active and dynamic.

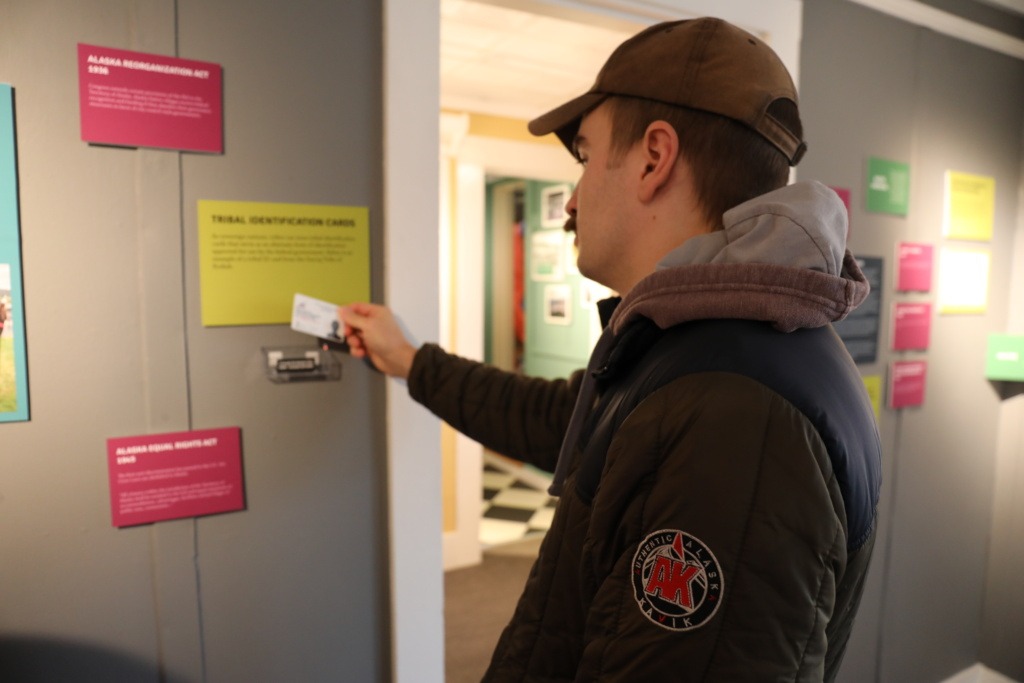

Our new model creates two temporary exhibits per year with key partners. Key partners propose the exhibit topic, and they take the lead in organizing the exhibit with the help of KHM staff, making them co-created exhibits. In co-created exhibits, community members are part of the key decision-making in organizing and creating an exhibit; community voice is a key aspect of the narrative and is present throughout the whole exhibit. Co-creative projects begin with community needs in mind as well as those of the museum. Projects like KHM’s new temporary exhibit program accomplish three primary goals:

- Give voice and be responsive to the needs and interests of local community members

- Provide a place for community engagement and dialogue

- Help participants develop skills that will support their own individual and community goals

A look at KHM’s Hunt, Fish, Gather, Grow: Exploring Food Security in Kodiak (2020-2022). This exhibit was KHM’s first effort using a co-creative exhibit model.

The Purpose of the Model

KHM recognizes that current events and issues are history in the making. We also recognize the idea that past events and historical legacies directly impact our Kodiak community, and critical engagement with the past fosters awareness of the origins of today’s events. To critically engage with the past requires investigation into past historical and institutional biases – what was collected, why it was collected, why we talk about these events, and what is missing from these collections and histories. History is not simple and straightforward; history was experienced differently by different populations. This investigation, through the form of community-based temporary exhibits, promotes an inclusive Kodiak history.

How To Be Involved

KHM’s temporary exhibit program utilizes an open call model for proposals. The link to the proposal form is here. Proposals are reviewed on a quarterly basis, and they are evaluated on topic, significance, and relevance to KHM’s mission.

Once a topic has been selected, KHM will work together with the proposer and/or a key partner (if not the same person) to create the exhibit. There will be a minimum of four meetings to develop each exhibit.

A Note About Proposals

KHM is looking to create exhibits with underrepresented communities in Kodiak. If you are submitting a proposal about one of these communities and not a member of that community, we ask that you partner with a community member or organization to create the proposal.

Additionally, proposals that contain more information are more successful in the proposal process. Proposals should communicate a clear idea and a beginning concept for the exhibit.

If your proposal is not initially successful, we ask that you revise and resubmit the proposal in the future.

DC Blog Post

Cama’i and welcome to KHM’s new blog! My name is Lynn, and I am KHM’s Curator. This summer, I was privileged to participate in the Summer Institute in Museum Anthropology (SIMA) at the National Museum of Natural History. This program is centered on preparing graduate students in anthropology to use museum collections as a source of data in research. While my participation in this program was under my PhD candidate hat, it had a major impact in my work at KHM, and I want to reflect on that in this first blog post.

My three takeaways from SIMA are:

- Museum objects are living, breathing entities.

- Objects connect out from the museum.

- Museums need to always ask, who is benefitting from this?, when organizing exhibits and programs.

Museum objects as living, breathing entities

And they had a life before coming into the museum. To illustrate this point, Joe Horse Capture (Vice President of Native Collections & Curator of Native American History and Culture at The Autry Museum) organized a series of lessons using lacrosse sticks. Horse Capture taught us how to play stick lacrosse using sticks he provided, and we played a game to get a feel for how the game is played and the role of the stick. It was a super fun lesson and very hard to play well.

In his following lesson, we looked at multiple lacrosse sticks from NMNH’s collections, and we were told to look for how the stick was used before coming into the museum.

This lesson showed us that museum objects had a life before coming into the museum, and they are still living, breathing entities. Their life in the museum is vastly different from the life they were created for, and we need to respect that previous life. We also need to critically think about how we recognize that these objects in the museum are still alive, and we need to feed them. This can be done by handling the objects or actually feeding them with offerings or rituals. We also need to view their full life stories, including their lives in the museum.

Objects connect out from the museum

These connections are both visible and invisible to visitors. While at SIMA, I looked at collections of baskets from southern Alaska. I kept noticing repeating patterns (looking very similar to KHM’s logo) on the baskets. Immediately, I likened it to our museum’s logo and where that logo came from. I then visited a new exhibit at the National Museum of the American Indian, and I saw these baskets made out of glass by Preston Singletary.

I would not have connected the baskets to each other if I had not worked with the collections in the NMNH. The baskets not only connect to each other, but to Tlingit culture and artistic traditions. Objects also connect out of the museum in terms of their materials, creation, and collection.

Led by Josh Bell (Curator of Globalization, NMNH), we “exploded” some objects. Exploding objects is the concept of looking at the object as if it exploded, and you could see all of its components. For example, if you exploded a beaded garment, you would see the beads, the materials used for beads, the garment material, and the sources of all these different parts (animals, components of glass, shells, etc.). You would also see the producers of the object, and the collector of the object. This process of exploding an object makes these multiple connections visible; instead of just seeing a solitary object, you see the object’s life story as embodied in the object.

Who benefits from this exhibit and program?

As colonial vehicles, museums have a legacy of taking objects from communities and placing them in often racist paradigms of collections care and displays, that would benefit the museum, not the community. The ongoing decolonizing museums movement is looking to fix this legacy through repatriation, increased access, educational programs, and new exhibits. As Joe Horse Capture prompted us, who benefits from these exhibits and programs? KHM has recently debuted our new temporary exhibit model, and in my next blog post, I hope to answer this question explicitly.

These takeaways will continue to figure into my work here at KHM, and I hope to share these efforts with you in future blog posts.

Long Haul Reflection

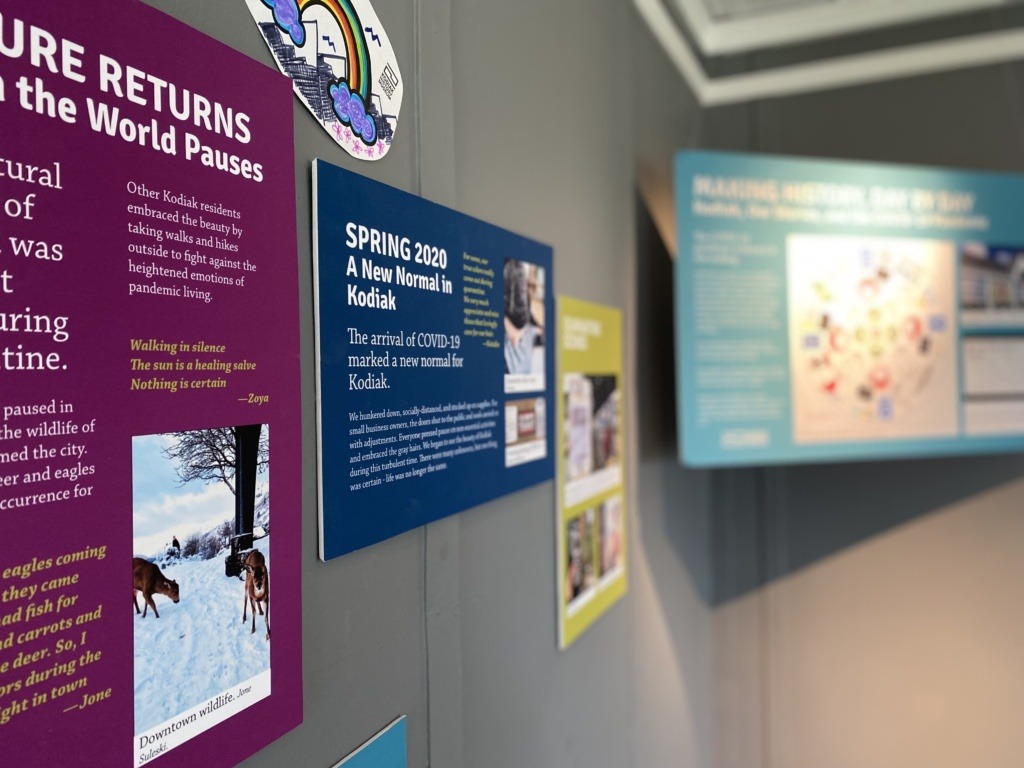

The Long Haul began in December 2021as part of KHM’s preparations for a new exhibit about the COVID-19 pandemic –Making History, Day by Day: Kodiak, Our Stories, and the COVID-19 Pandemic. KHM sought to initiate a conversation about how the pandemic impacted and continues to impact life in Kodiak. The pandemic was an uncertain time filled with upheaval, anxiety, and differing political stances and opinions. A forum was needed for everyone to reflect and look forward to the future together. Enter KMXT and the partnership that became the Long Haul.

It was a privilege to facilitate these conversations and listen to people tell their stories –good and bad. KHM hopes that you enjoy these programs and that they provide a sense of communal reflection as this historic pandemic turns endemic to life.

Long Haul Episode 5

Talk of the Rock – Kodiak Collective

KMXT’s Dylan Simard is joined by Lynn Walker, Sarah Loewen Danelski, and Natasha Zahn Pristas to discuss the Kodiak Collective art installation.

Long Haul Episode 4

Hosts Mike Wall and Lynn Walker talk with guests Mike Murray of Safeway and Dan Rohrer of Subway about the impact COVID has had on their lives, their businesses, and supply chain issues –what’s happening now and what’s coming next.

Long Haul Episode 3

Hosts Mike Wall and Lynn Walker talk with guests Susan Philo, Clinician at Providence Island Counseling Center, Heidi Barrett-McNerney, Director of Behavioral Health at Kodiak Community Health Center, and Jocelyn Figureid, Behavioral Health Clinician at Kodiak Area Native Association about mental and emotional health throughout the pandemic and community resources.