March 30, 2017 marks the 150th anniversary of the US purchase of Alaska from Russia. To commemorate this sesquicentennial, the Alaska Historical Commission funded a research project by the Kodiak Historical Society into the history and records of Fort Kodiak at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. This post is the result of that research.

After the US Purchase, for two years (1868-1870) Kodiak went by two names: St. Paul and Fort Kodiak. Fort Kodiak was one of six Army posts established in Alaska following the purchase. Alaska was purchased without any discrete plan for a civil government. Many presumed that Congress would soon pass legislation to give Alaska some form of government. Initially, it was decided that Alaska would be managed as a military district. General Jefferson C. Davis was sent north as the first military commander of the Military District of Alaska. He was responsible for assuring peaceful relations between Alaska Natives and white settlers and was supposed to encourage trade. Davis established military posts at Sitka, Wrangell, Tongass, Kenai, the Pribilofs and Kodiak.

Battery G of the Second Artillery was sent to establish Fort Kodiak. Battery G had recently fought in the Civil War. These soldiers had participated in the Battles of Bull Run, Glendale, Malvern Hills, Fredericksburg, Salem Church, and others. After the war, they were dispatched to the Presidio in San Francisco and from there, received orders to head north. Consider, these men carried memories and combat experience from the Civil War with them to Kodiak. The ninety-five enlisted men and three officers who were sent to Kodiak were not a homogenous group of Yankees. Many of them were immigrants, hailing from Germany, Ireland, France, Venezuela, and elsewhere. These veterans were American, but, like the people in Kodiak whom they would soon encounter, some of them had become American only recently.

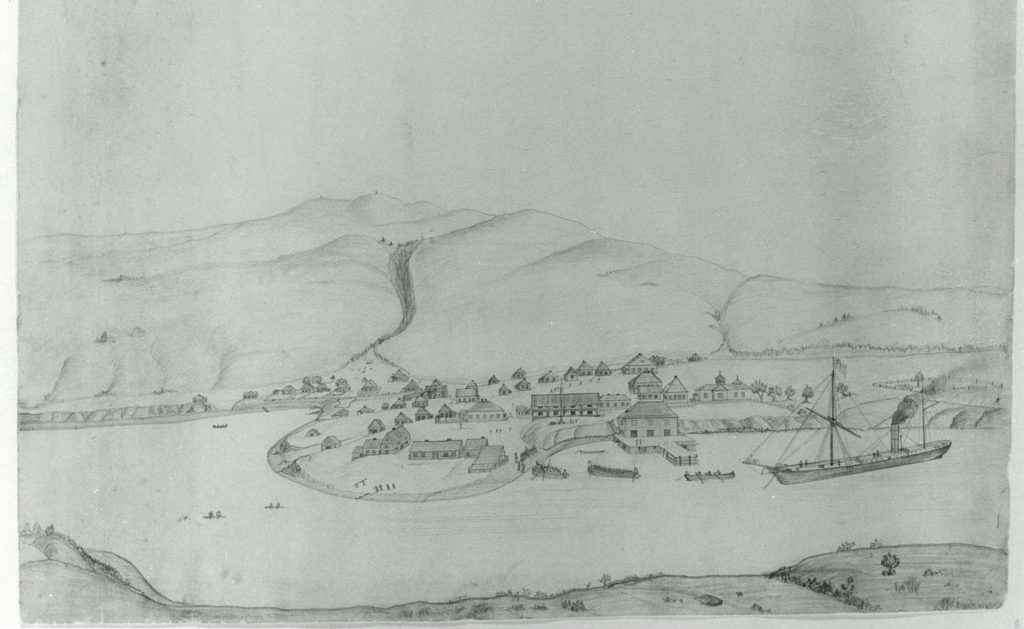

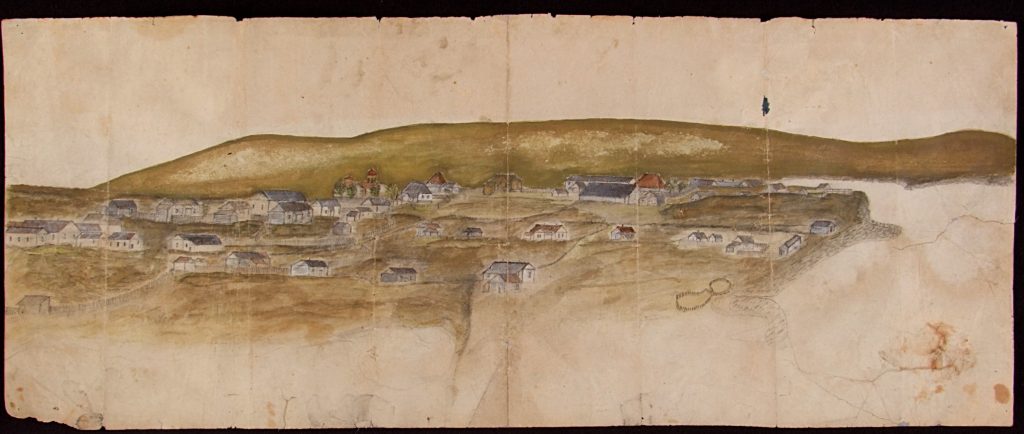

These ninety eight soldiers, some with wives and children, left from one island, Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay, aboard the Atalanta and arrived at another island, Kodiak, on June 5, 1868. The soldiers encountered a Creole village at the base of Pillar Mountain known as Pavloskaii Gavan, or St. Paul in English. Creoles were part of the Russian estate system; the social, economic and political system in which people were classified. Creoles generally were of both Russian and Native heritage, the children of Native Alaskan mothers and Russian fathers. During the Russian period, villages around Kodiak were segregated, with those classed as Natives in specific villages and Russians and Creoles living in other villages. Kodiak was a designated Creole village.

When Battery G arrived, Vasilii Pavloff was the Lieutenant Governor of Russian America. Until the Alaska Purchase, he had been in charge of the Kodiak region for the Russian-American Company. His wife, Pariscovia, was a Creole from the Archimandritov family and together they had a large family.

According to the provisions of the Treaty of Purchase, Russians and Creoles either had to move to Russia within three years or they could stay and become citizens of the US. The vast majority of ethnic Russians returned to Russia with their families, including Vasilii and Parascovia Pavloff. The motivations of these individuals is a lingering question, unaddressed in the available English sources. Army records do indicate that several Creole men took the oath of citizenship, including the couple’s son, Nicholas Pavloff.

Nicolas Pavloff also provides us with one of the only secular sources written by a Kodiak resident describing Kodiak while Fort Kodiak was in operation. In 1903, he described life in St. Paul alongside the Army for the Kodiak Baptist Orphanage’s Newsletter:

They had built soldier’s barracks, guard houses and all necessary buildings for a military post; and we had military law. At sun rise and sun set one of the brass pieces was fired, which scared the natives and wild animals around surrounding bays. If a man stole or fought he would be placed in guard house, placed on a ball and chain and given work outside. So all these new rules and regulations made the people behave themselves straight and quiet.

Trade is something that only comes up sporadically within the military records, even though it was a busy time of commerce in Kodiak. When the US gained Alaska, the firm known as Hutchison, Kohl and Company purchased the assets of the Russian-American Company. This included company buildings, warehouses, and all of the goods within the warehouses. Frederick Sloane Sargent was an early hire by Hutchison, Kohl and Co, and he was dispatched to Kodiak in April to take stock of the company’s new assets. Note that by the end of 1868, Hutchison, Kohl and Co had reorganized as the Alaska Commercial Company, or AC.

It appears that Sargent took advantage of his early entry in Kodiak and his knowledge of Russian-American Company practices when he told Alutiiq hunters that they could only sell their furs to him. Previously, the Alutiiq could only sell their furs to the Russian-American Company. After the Purchase, this was contrary to American principles of free trade.

A letter was sent to General Tidball from Kaguyak, complaining about this misinformation. Within it, the writer said that Sargent threatened severe punishment to those who sold furs elsewhere. In response, General Tidball sent out 10 letters of free trade to Kaguyak hunters, stating the following:

To all whom it may concern… The bearer, Nicola Chunackooshi, is free to trade his furs of fame to anybody he chooses in exchange for money or trade and each trader has an equal right with all others to trade with him in all articles not contraband.

There were other adjustments to daily schedules beyond the startle of morning reveille. Kodiak residents were still operating on the Julian calendar, and their day was still oriented towards Russia, not the US, while the servicemen were on the Gregorian calendar and operating to the east of the international dateline. As a result, when it was Saturday in the minds of the soldiers, it was Sunday for the rest of Kodiak.

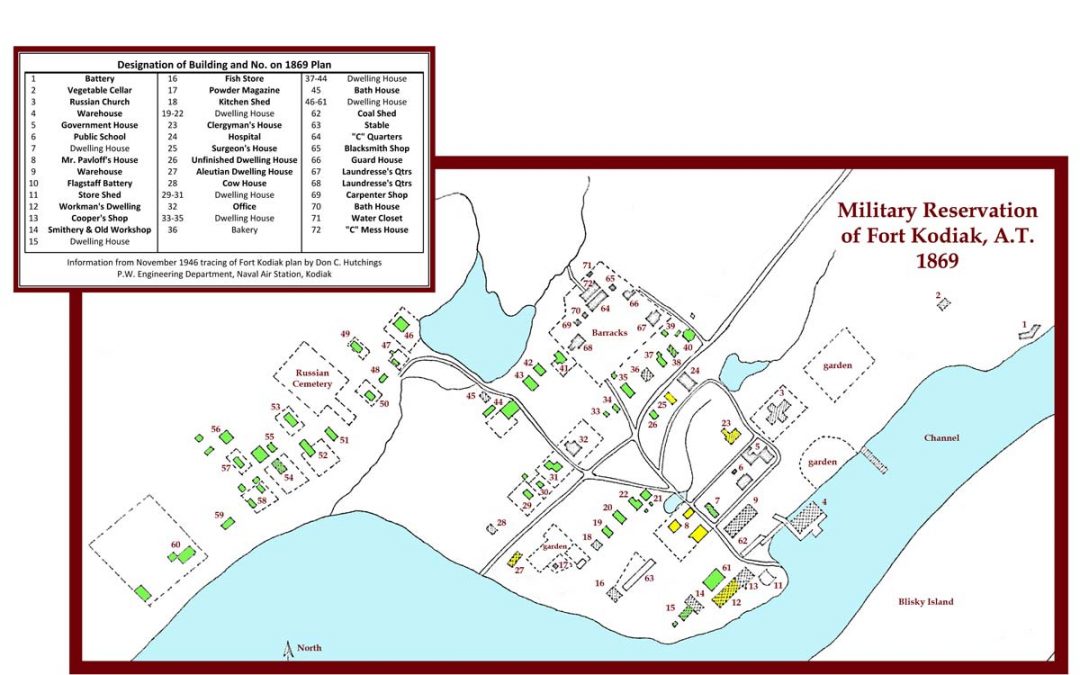

Lt. Eli Huggins and Lt. John Campbell put Battery G to work, turning St. Paul into Fort Kodiak. They platted a one mile square military reservation, which today roughly corresponds to the area behind El Chicanos, near the corner of Center Street and E Rezanof Drive. The servicemen built roads and barracks, and made improvements and repairs to the previously Russian buildings that now belonged to the US Government. They fed and slaughtered cows, worked in the cook house and the hospital, and spent lots of time procuring, chopping, and carrying fire wood. They also opened a school.

Court martial documents describe transgressions around the fort. Alcohol was a menace, both to the soldiers and the local people. People stole from the store, owned by Herman Shirpser, and were arrested and placed on ball and chain as punishment. The most serious infraction was committed by Private John Finnerty. He stole six sea otter pelts from the store and attacked a soldier, stabbing him near the heart. Finnerty was sentenced to hard labor with a 24 pound ball and chain for the duration of his military service, given a dishonorable discharge, and had to serve three years in prison once he left the military.

American capitalism had come to Kodiak, as well as American celebrations. The Fourth of July was first celebrated in Kodiak in 1868. Soldiers were given light duty and a national salute of 37 guns was fired that day at noon. But the celebration got out of control. The Alaska Herald reported the following:

Some drunken soldiers took possession of a couple of Russian cannon, which had not been used since the time of Catherine the II. The caliber of the cannon was suited to a half pound charge or powder, but those patriots(?) loaded them with two pounds and fired away. The consequent was one burst, scattering the fragments in all directions

A lasting legacy of the short-lived Fort Kodiak was the marriages between American soldiers and local women. Vital statistics of the Russian Orthodox Church from the period show that ten soldiers were married in the church during their assignment to Fort Kodiak. The military records correspondingly show oaths that the men took before their weddings, swearing that they were, indeed, unmarried. Some of these newlyweds shipped out with the soldiers on September 18, 1870 when Fort Kodiak was decommissioned, but others did stay in Kodiak and start families.

It was not a thrilling time for the soldiers stationed at Fort Kodiak, but for local residents, it signaled a time of massive change. Kodiak had new markets for its goods, but also a new trading paradigm that was a difficult adjustment for many. Though Kodiak was primarily governed by businesses during both periods, the Russian American Company emulated the close scrutiny and paternalistic involvement of the Russian government while the Alaska Commercial Company was given close to free reign and emulated more American ideas of free capitalism and independence. After Fort Kodiak, the US government was barely involved in Kodiak’s governance; Alaska wouldn’t become an American Territory until 1912 — 45 years after the purchase.

There are two remnants of Fort Kodiak that persist today. The American Cemetery on Mill Bay Road was established by Fort Kodiak and eight soldiers are buried there. There are also several Kodiak families who can point to the Alaska Purchase and the establishment of Fort Kodiak as the moment when they first gained an American ancestor, their legacy in helping Kodiak become American.